The impostor syndrome – whereby perfectly competent people struggle to attribute their achievements to their hard work, skills, or wit – can show as a specific form of self-doubt.

In the past week I have had nearly the same therapy/coaching session three times with three different clients:

- An executive woman in a government agency who can’t say no to requests because she doesn’t want to disappoint her new boss – and so she stays up until 2 am to finish her work

- A senior-level manager in an advertising company whose manager is unhappy with the choices he’s making about how he’s managing his time

- A graduate student in architecture, about to submit her master’s project, whose thesis advisor questions her approach to the project

There are many ways to look at these situations, of course. One might view those as “varieties” of the impostor syndrome mentioned above. One thing is to consider how the managers of these three individuals are creating the conditions for insecurity and doubt to emerge amongst their direct reports. We are all affected by the people around us, especially our manager, a person who evaluates us and whose evaluation can even affect our livelihood.

And yet.

The truth about how we suffer is it’s actually very personal, and usually less dependent on external factors than we realize. So it might be tempting to blame the boss – and in some cases, demanding, perfectionistic managers are indeed a big part of the problem. But whether we’re in coaching, therapy, or doing our own reflective work, the only thing we can really have a chance of influencing is our relationship with others and most importantly, our relationship with ourselves.

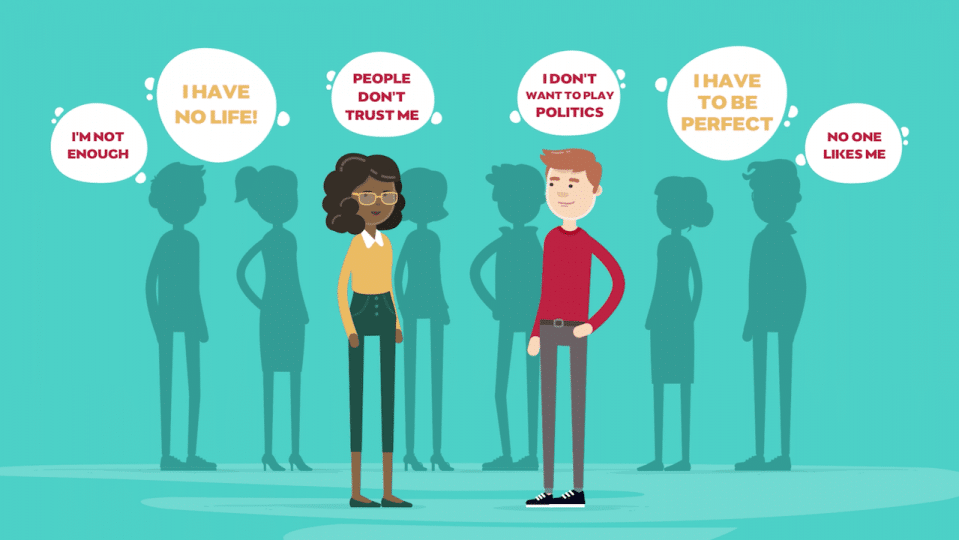

In each of these cases, the thing these clients have most in common is an enduring and driving belief system within themselves of not being enough. That translates to a sense that they are never doing enough, rarely performing enough. What is also shared amongst these individuals too is a deep desire to be liked, and valued, by their managers.

Growing out of a deep-seated pattern like this – an “operating system” or script—starts with building our self-awareness. We start by noticing when and how often the belief system shows up, and we look at the effect it has on us. In all of these situations, my clients could see that this drive to perform and to receive approval, was long-standing in their lives and showed up in many ways, quite often. The effect is a nearly-compulsive drive to perform, often beyond physiological limits – resulting in fatigue, isolation, anxiety, depression, and at times, illness.

It’s also important to recognize that beliefs and behaviors like this arise out of circumstances, usually early in our lives, and we often come to these conclusions for very good reason at the time. As children, we make observations about how to be in the world to stay safe – and performing and being compliant are often reliable ways to get others to approve of us. But we get into trouble, as adults, when these ways of being are anachronistic – and show up chronically, and out of our awareness.

Coaching work varies for each person – but our starting point is looking at the origins for these belief patterns. We also bring our attention and care to the younger version of ourselves who came to this conclusion about the world, and who we had to be to survive.

We learn to feel, and experience, in our bodies, where the belief lives physically within us and experiment with breathing and mindfulness to understand how these patterns now live in us, somatically speaking.

We might even engage in dialogue with our younger self, and bring compassion and understanding to the part of us, with a more primitive and less developed brain, that made a conscious or unconscious choice to live in this way.

We explore the costs (and the benefits) for being driven by this belief system, and we play with the notion of choice – do we want to continue to live this way, and if not, what might it look like to relate to ourselves and others differently? We explore what it means to first please ourselves and we experiment with giving ourselves the internal support we often lack to say “I’m enough” and “this is enough”.

The road to growth and emotional maturity may be slightly different for each of us – as are our specific origin stories – yet the commonality of the belief system of not being enough has an omnipresence that is significant – it’s also distressing for anyone who lives with it, and grows aware of its negative effect. Feeling the impostor syndrome serves us as a pointer to explore our true and mistaken sources of self worth and ambition.

I would be lying if I said I didn’t know this place inside of myself too – a space that can compare myself to others and temporarily feels I am enough until a moment of doubt emerges where I start wondering again. I practice giving myself the patience and love and affirmation I recommend to my clients – and with time I have found there is more space and less self-judgment. We are all in this together.