Our clients know we are big fans of Kegan’s and Lahey’s work on adult development theory. We use this framework in our leadership coaching and team development work because it really brings a conceptual angle to our real-world experience that personal and professional growth are deeply related. (More about it here…)

I republish below a revised article I wrote at several years ago for Forbes.

In my coaching practice, especially in transition coaching contexts, I hear clients incorporate phrases into their speech like “stepping into my own” or “developing my leadership voice”. It’s something that’s on the minds of many: a desire to be more true to oneself, to act “more grown-up,” not just driven by external or our superego’s expectations but rather by an inner value compass that feels true and meaningful.

All this seems important to many of my clients, but it’s also a bit obtuse. Vague hopes and intentions usually don’t translate well into new behaviors — so let’s break this desire for being more true to oneself and following one’s passion down in ways that allow us to take action.

We are well aware that children go through distinct developmental stages as they get older. For instance, your 3-year-old won’t throw a hypothetical question at you; your 14-year-old most certainly will. But what does it mean to be an “adult”? Are we an adult once we hit some magical milestones? And then what?

Adult development theory has been around for more than three decades and recognizes distinct developmental stages in adults — much like in children. Rather than a “this is it” fully formed adult mental stage, the adult self is an evolving self.

Creating terminology and a framework to describe this evolution is a key contribution of Robert Keegan’s, a retired professor in adult learning and professional development at Harvard, whose work with Lisa Lahey and others presents the adult self as a self marked with successions of advancing mental logics.

In relation to leadership or our ability to be effective team members, people who are more conscious and self-aware are better problem-solvers, collaborators, and leaders.

That’s not just a hypothesis. One study, for instance, showed a strong correlation between a person’s effectiveness as a leader and that person’s way of processing mental complexities, such as different points of view or competing objectives.

Kegan’s and Lahey’s model distinguishes three stages of adult development: the socialized mind, the self-authoring mind, and the self-transforming mind.

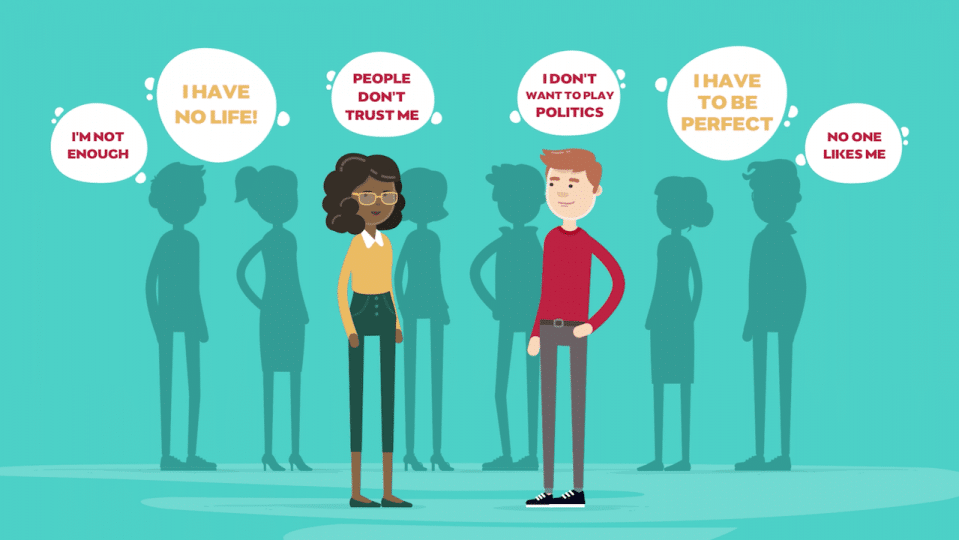

Most of us — about 75% of the general population — live predominantly from a socialized mind. That means we tend to seek external direction, are shaped by definitions and expectations of our environment and try to adhere to identities we formed earlier.

Compare that to the self-authoring mind where people align with an internal sense of direction and inner seat of judgment. These people are able to step back enough to question expectations and values, take stands, set limits, and solve problems with independent frames of mind.

For now, I won’t even touch the self-transforming mind stage that takes our ability to mentally process complexity and interdependence to a whole other level.

“Let’s be more adult” will mean for many of us being less in a socialized mindset and more in a self-authoring mindset.

Let me give you two examples from my coaching practice of what this could look like.

I am working with Julia, a top-level executive in line for a C-suite role. Part of her challenge is to build authentic influence among her executive peers — and part of that challenge is to let others know what she stands for personally.

Julia’s leadership vision is pretty clear, her technical acumen beyond doubt, but people wonder what drives Julia. What is this about for her? Is this money, status, recognition? Something else? The problem is that Julia doesn’t really know for sure, either. She had built much of her professional success on her smart, drive, persistence, and some internalized parental expectations to “be in it to win it.” Being “more of an adult” for Julia challenges her to step into her leadership that rests on her own value compass and sense of purpose vs. demonstrating her ability to execute someone else’s agenda.

Another example is Thomas, a leader of a global function in a multinational company that recently went through a merger. Thomas, in his late 50s, is ready to step off the career treadmill. He knows this with certainty. What he doesn’t know is what’s next. In our sessions, he tries to “organize” his transition, feels he is not effective in managing it, too slow in setting himself up for what’s next — whatever that may be.

Finally, Thomas had an insight: He measured this whole challenge of transitioning out of his professional identity of many decades in just the same way he managed his responsibilities — plan and execute with efficiency, meet defined success measures, rinse and repeat. Realizing that his situation was new and that he would have to define for himself what his next life chapter was about was a step toward living from a self-authoring mind.

I invite us to seek and deepen our own ways to being more adult — clarifying and acting on what we know is true for us, honoring a sense of self not based on achievements, exploring our interconnectedness with others and the world, and reflecting on the limits of our personal beliefs and ideologies. And wondering, above all, what truly matters for you?