Let’s just assume you tested your IQ and you came out above 130. That, technically, makes you a highly-gifted person by many definitions social or organizational psychologists use. It also puts you disproportionally at risk of struggling with career issues if you choose to work for a bigger organization.

High intelligence doesn’t necessarily mean career success: Many organizations have observed that “high potentials” can rise fast – only to later fail or crash spectacularly. What is going on?

A recent organizational psychology study (“Correlations between high-intelligence and career-related personality attributes”) provides some interesting answers beyond the true but unspecific request for improved social skills. Assessing a sample of 500 highly-gifted and 2,500 average-gifted employees on an inventory of 14 attributes in four categories of career orientation, work behaviors, social competence, and psychological constitution, the study found significant differences in 13 of the 14 areas.

Exceptionally smart people, it turns out, really “tick differently” – which may help explain why they can come across as too fast know-it-alls with a competitive (or self-absorbed) perfectionist streak.

Let call the IQ 130+ group the HGG (highly gifted group) and the baseline group of employees with IQs below 130 AGG (the average gifted group).

- HGGs want influence – not power

HGG are five times less likely to be motivated by leadership positions than AGG. But they are more interested in influence to effect change.

HGG specific behaviors to exert influence may be seen by others as a grab for power – and lead to negative repercussions. If you are an HGG, you may want to create extra transparency about your motivations – and ensure your boss or competitive peer that you are not aiming for the corner office. - HGGs put mind over matter

HGGs are four times less likely to be action-oriented than their AGG colleagues.

As an HGG avoid being seen as “all talk no action”. Monitor the degree of (im-)patience others exhibit towards you. If you don’t act, others will. A good idea acted upon and continuously improved is better than the perfect idea that never sees the light of day. - HGG may put what is true over what is right

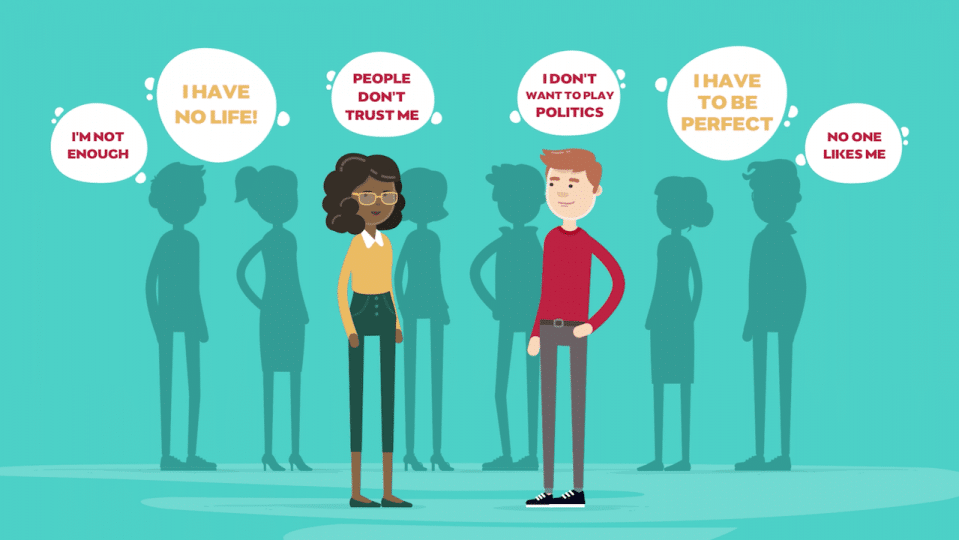

HGGs do exhibit lower levels of social skills than their AGG peers. They are less sensitive to the needs of others and their impact on them. They are also less able to initiate contact. As a result, HGGs may risk to stand on principle even when it hurts their ability to generate buy-in to their vision.

Well, don’t stand on principle. Initiate contact. Accept that you need to “socialize” your idea. As an HGG you may be exceptionally smart – but most likely no one person has all the answer. - HGGs are not exactly team players

HGGs are significantly less team-oriented than AGGs. Perhaps HGGs experienced one too many times that left to their own devices they solve problems more efficiently. But here is the rub: Most certainly, it will take many to drive and implement a relevant social or business idea. Having the “best” solution to a problem doesn’t mean you get it done in real life. Buy-in comes from participation.

As an HGG, consider the “extra” time others need to come to a conclusion they can endorse as an investment: You will save that time later when “your” idea requires others for implementation.

Despite their talent – and perhaps just because of it – HGGs are emotionally less stable. This is in line with the “prima donna” stereotype we find in organizations: They exhibit less emotional balance, lower degrees of resilience under duress, and lower levels of self-confidence.

The single most powerful question – if there is one – for a highly-gifted individual seeking more organizational influence is this:

Do I want to be right or do I want to be relevant?

While HGGs are less likely to build social support systems they should actually make an extra effort to do just that as their need for social support tends to be higher than average to bring traction to their vision and talent.